Posts in Category: 2010

The Bastard of Istanbul

These last couple of days I have had an adventurous craving for food I don’t know how to pronounce, and basically don’t know what is. It is due to my latest gobble of world literature that this passion has taken a hold of me so strong I am inclined to postpone this semesters’ uni start and go to Istanbul and sit in a café, sipping strong coffee and eating little treats while watching the loud, bustling city roam by.

Elif Shafak‘s ‘Bastard of Istanbul’ has had that effect on me. It is a story of two families, one Turkish and one Armenian, who become intertwined by fate and a little human exploratory curiousness. For the novel Safak almost ended up in jail for insulting Turkishness, by raising criticism, and dealing with the painful past of pre-modern Turkish state, that of the Armenian Genocide.

The story is pushed forward by a female Weltschmerz. All the men die young in Turkish family, so they play a minuscule role in this matriarchal narrative. But the women none the less become a miniature of the diversity and complexity that forms the young Turkish modern state. There is so much anger bundled up and exploding on the pages and it is mystified by a touch of myth and tales. There is the question of Diaspora in the Armenian Americans – a young woman who is so aware of how her whole identity is tied up with the horrible events that is being inherited down generation by generation, but at the same time it is so foreign to the younger generation who have never had a real life experience with the country where the Armenians faced so much adversity. And then there is the Turkish modern female, who wishes no past at all, and in effect (as she is the bastard of the title) can deny having a past, at least on her father’s side. These two women, Armanoush the Armenian and Asya the Turk, meet in Istanbul and together they start on a healing journey. In itself it is enough to initially activate your gag reflex, but aside from the prophetic mission to mend the gap between Armenian and Turkish affairs there is a lot of positive things to be said about the novel. First of all, there is obviously (a writer facing jailtime is always a good indication) some things that need to be said and dealt with. And not just between the Armenians and the Turks, but the East and West too. The sense of deprived ancestry can both work for you to keep peddling forward, but it can also hinder your (e)motions. And second, the tonality in the novel is very aesthetically beautiful – there are sections that are a bit too blatantly cut out into bits for the reader to follow, which could be a weak spot of the author who feels the need to get a specific point across – and I love that the story in the novel can be interlaced with something so homely and sustainable as food. It is like a spin off of Isabel Allende’s ‘Aphrodite’ where food becomes the link in her narrative and acts as (surprise, surprise) an aphrodisiac. What I am clumsily trying to get at here is that food connects people, and it does too in this novel. When Armanoush meets Asya’s family she instantly recognizes the foods that are served because she knows them from her Armenian grandmother, and this acts as a connection between them and a safe starting-point for Armanoush to introduce her past and self to Asya’s family.

As a little titbit there is a recipe in the book, and there is a reason all the chapters are titled after something edible. And underneath this seemingly innocent layer lies so much more that can awaken an adventurous spirit.

Related articles by Zemanta

- Armenian-Americans Sue Turkish Government, Banks For Century-Old Mass Killings, Seized Assets (huffingtonpost.com)

- Elif Shafak: Motherhood is sacred in Turkey (guardian.co.uk)

Sara Stridsberg

I had some good news today.

Sara Stridsberg is out with a new book called ‘Darling River’, published in Sweden in early 2010 and just translated to Danish pending appearance on August 20th. I, however, (sorry Danish publishers and bookstores) will shoot my future career in the foot and buy it in Swedish and on the internet! My fingers were tingling just by the thought of this book as I was reading an interview with the author in Weekendavisen’s book section. And at one point Stridsberg explains her writing process and I knew just what she meant, only with me it’s in regard to my reading process.

When I am writing on a novel I always have the feeling of being away in a dream for a couple of years and afterwards I almost can’t remember it.

The thing with dreams is (as Mr. DiCaprio says in the movie Inception, which I went to see the other day btw) you are just there in the middle of the dream, all of a sudden. And as with dreams, literature, for me, behaves in a similar fashion. I couldn’t tell you how it started, I can’t remember every detail, there is often just the feeling afterwards of having felt something, which in reality is really blurry, and I really have to concentrate if I want to recollect details. But the bigger picture is so much more colorful and vibrant.

Solanas

I read Sara Stridsberg’s ‘Drömfakulteten’ about two years ago, which is a “literary fantasy based upon Valerie Solanas” – the girl who shot Warhol – and I was blown away by the style in particular, but also the very gripping story that interlaced the pages. There is the factual person Valerie Solanas, and then there is Stridsberg’s fictional Valerie Solanas. What’s so great is that factual Solanas may have been the stepping stone for the fictional one, but neither is in the others’ debt. Imagine a spoon and a bowl of water; you dunk the spoon in, making ripples in the water, and take a very little percentage of water out, drinking it and leaving the water disturbed, touched. With reading I feel like, on it’s own, the pages with signs on them are meaningless and still, but as soon as I read a page it is in my head, occupies my thoughts and forms my consciousness. Stridsberg has translated the SCUM-manifesto, written by Solanas, before writing ‘Drömfakulteten’, so it is a really interesting process to figure out how Stridsberg has read in between and on the lines to create her ”fictional” Solanas. The novel is raw and shifts between the past, present and thoughts of Solanas’, who carries herself with a sense of self-rightiousness of a radical political activist. At the same time it is also a very vulnerable and lonely novel. There is so much unresolved emotional baggage that dart out of the story and the pain is most explicit when Solanas is conversing with Silkboy, her companion and ally. It is a dark universe that sucks you in, and questions of sexuality, wronged and wrong are recurrent in the novel, forming a foundation for the pained individual.

Stridsberg

If you read Danish and are interested in Stridsberg’s authorship, I would recommend this interview, which is to be found in Weekendavisen’s no. 32 – August 13 2010. And I would definitely recommend ‘Drömfakulteten’ (of course, if you like stream-of-consciousness styled literature, Valerie Solanas, sexual politics, the tormented individual, take your pick!)

I can’t wait to receive my copy of Darling River, but if anyone has read it out there, feel free to make your impression known here 🙂

Processing 9/11 – a Foer experience

I don’t remember what I did at 10 o’clock in the morning. But I remember the afternoon. That’s when my little TV in my little dorm room was turned on because I had received a very odd text from a friend, and it wasn’t even April 1st. It felt like April 1st, a very cruel Fool’s Day. But it wasn’t, it was 9/11, and from that day it became an expression, no need for explanation, it was just 9/11. I don’t remember what I did at 10 o’clock the next morning, but I do remember the afternoon past.

The reason I have gone back to this date is because I have just finished reading Jonathan Safran Foer’s ‘Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close’. I got it after reading ‘Everything is Illuminated’, because Foer’s style of and topic really hit home with me. And I was not disappointed. I was thoroughly plowing through a child’s universe filled with sorrow and a silver lining.

Center to the story is the little boy Oscar, a little boy who feels everything, incredibly and extremely. The loss of his father in the 9/11 attacks on the Twin Towers sends him on a scavenger hunt around New York in search of answers; answers that can tell him how his father died, what he should do, how he should react, who he is. His special bond with his father is severed and the need to find a way to process a reality that does not even seem real takes over. The traumatic loss is omnipresent in everything he thinks and does, and pervades every single page of Foer’s 355 pages novel. Everyone Oscar is in contact with is seen through the lens of loss and solitude. But he has his imagination and determination, which works both for and against him, it drives him towards seeking answers.

The immediacy of the storyline, whether it is Oscar’s travels through the boroughs of NY or his granddad’s letters, leaves me breathless. I think it is partly because this is the first time I have read a novel that is centered around the aftermath of 9/11, that is, not America or the States as a democratic nation or Western power attacked and fighting the Axes of Evil, but a novel about the personal experience of the attack; a boy who misses his father, the child’s take on 9/11. And Oscar just won’t let this event go, he can’t:

It makes me incredibly angry that people all over the world can know things that I can’t, because it happened here, and happened to me, so shouldn’t it be mine?

The novel works in circular patterns. The processing of the 9/11 trauma is underlined by a trauma of 20th century Europe: WWII and the bombings of Dresden. Oscar’s father ‘leaves’ him and his father left him before that. I get the feeling that everything works in weird, not necessarily connected but none the less, thoughtful patterns. You find yourself wishing that everything is connected in the great cosmos of life, regardless of time, space and human interference.

But Oscar’s experience is not the only thing that forms the novel. Foer has used a lot of techniques that make the novel more than a traditional “read letters = understand meaning” type of novel. There are pages that are filled with red ink circling random letters (a reference to how Oscar’s father spellchecks the New York Times), pages that are empty save for one lone sentence (as Oscar’s grandfather is incapable of speech, cause unknown, and communicates with “yes” and “no” tattoo’s on his hands or by writing everything down wherever he can), and pictures of some of Oscar’s different impressions. This is, in my opinion, both good and bad, because there is a lot of it going on in the book, and you need to see it both as part of, but also separate from the rest (if that makes sense at all 🙂 ). Foer’s style is secure enough in itself without all these gadgets, but it does add a little extra when you can reverse 9/11 at the end, and make a man fly upwards rather than falling down towards the ground, simply by flipping the last 10 pages.

Euripides’ Medea

My holiday books are in a dead heat with books I have discovered in my mom’s bookshelves. I could have told myself that books were not a necessary item to bring with me on a trip home, but I got greedy. The latest raid left me with seven books in each hand and three in front of me. But incredo-woman as I am in the field of literary vice, I am able to multitask, so this weekend I have been reading Herta Müller’s ‘Der Mensch ist ein grosser Fasan auf der Welt’, Virginia Woolf’s ‘The Waves’, and Euripides’ ‘Medea’. Three completely different books, both in style and theme, and all three keeping me on my toes.

MEDEA

I finished the copy of Medea first – it wasn’t that long, so it was a good night’s read – which I found out both my mother and my uncle read in high school. As I was reading it, I thought about the famous line “Hell hath no fury like a woman scorn” (originally from W. Congreve’s play ‘The Mourning Bride’ from 1697, but often misquoted as a Shakespearean line, it goes like this: Heaven has no rage like love to hatred turned / Nor hell a fury like a woman scorned.) I also thought about how you often toss it out whenever a woman gets angry to disarm or delegitimize a miffed out female. In the context of Medea it is also relevant to mention that Fury is a female spirit of punishment in Greek mythology (The Furies (Roman mythology) or Erinyes (Greek mythology) in the Underworld punish the guilty, and are avengers of violations of natural order, among these kinship murder). The story of Medea in Greek mythology is this: deeply in love with the warrior hero, Jason, sorceress Medea agrees to help him in his quest as long as he promises to take her with him and marry her. As many mythologies go, there are a lot of hindrances and creatures with different divine powers to be conquered. In the beginning of Euripides’ tragedy Medea, although now married to Jason, has been scorned by him in favour of the daughter of king Creon, in order to help his political status. So enraged by this treachery she wows to take a most gruesome revenge. Medea is known and revered in the land as a wise woman, and Creon genuinely fears her retaliation, so he exiles her, but she persuades him to give her time to find a new haven. Unknown to him, she has just bought time to concoct a plan to hurt Jason by killing his daughter. Jason himself goes to her to smooth things out, the first time of no use, but on the second visit she leads him to think she has forgiven his actions and wants to give his wife to be a present of a dress and a coronet. In fact, she has poisoned the clothes and in the most horrific way Glauce (Creon’s daughter) dies. When Creon touches her he is also killed by the poison. Two down, two to go, as Medea has no intention of stopping here. In order to really get to Jason, she also kills off their own children.

The tragedy is truly worth the read, it is pure spears to the heart, and the dialogues are beautiful, and each sentence is laden with moral and ethical food for thought. It truly is tragedy in its truest sense. The character of Medea, also the interpretation Euripides makes, has been an inspiration and topic of many men and women throughout history, not only literary history, but living history in general; her actions scolded, her passions revered, her sorrow felt and discarded, she truly is a being of great magnitude. The sacred role of motherhood is contested, she is cast into the role of a monster, and yet maintains an aura of pride about her. And there is always the question if her intelligence is a stumbling block or an asset – is intelligence of the mind or heart, or maybe a harmonious fusion of the two? Throughout the whole ordeal she holds her head high, places the full blame of occurring events on Jason, and seeks justice for her lost honour. She truly is complex, and although the play in itself, as I earlier said, is a quick read, the story is not easily out of mind. I suspect it will not be long until I go through the play again, and I would really love to see it played out, even if it could never stand ground with the impressive characters and scenery I have built up inside my head 🙂

Different images of Medea

Scene from a South African adaptation of Euripides’ Medea. Performed by Jazzart Dance Theatre during 1994-1996.

Directors: Mark Fleischman and Jennie Reznek

Photographer Ruphin Coudyzer.

Choreographer – Alfred Hinkel

Composer – Rene Avenant

Actor – Bo Petersen (Medea)

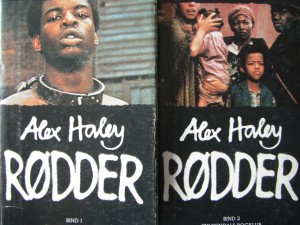

Nostalgia: Alex Haley’s Roots

When I was a kid I used to raid my mother’s book shelves after I had emptied the village library, and my own book club books were turned over about 4 times. Most of the stuff I read I couldn’t really fully understand in all their complexities, but there are a couple of books from her shelf that have stuck by me for all these years. One of these books was Alex Haley’s ROOTS.

To sum it up in too few words, the book is a family saga, written by Mr. Haley about his ancestry and as a symbol of the Afro-American slave history. The name Kunta Kinte has buried itself into my memory and is a symbol of both the knowledge I, since this book, acquired of Afro-American slave history, and the focal point from which I have read literature of this nature. Alex Haley researched his family history for over a decade in museums and libraries around the world. What really stuck with me was when I read in the the last chapters just how important this story was for Mr. Haley, as he climbed into the cold cargo hold of the ship he travelled with from Africa to USA. He spent all ten nights down there, naked and freezing, in order to get an inkling of what his forefather went through, even how minor his experience could be compared to that of Kunta Kinte and so many of his country men and women. This sat with me, the amount of dedication to the story and how important it is to acknowledge something in order to process it. As much as I owe this book, and books like this one much for helping to build my character, sadly, this book also introduced me to an experience that I wish I could have lived without: shame over the color of my skin – shame over my cultural heritage and apparent standing in life. Irrational as it may be for a 12 year old girl, stuck in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean without ever having experienced or thought anything that could resemble any discriminatory act, the weight of the connotations that followed my skin color was heavy. How this could even be true, that you could take a human being, put them in shackles, transport them in pitiful conditions across the Atlantic Ocean, using them and abusing them in every manner, was so horrible a fact to come to terms with. I don’t know if the shame is a collective shame of the caucasian race in the Western post-modern world, or if it’s just because I’m an easy knock out, but it was very real during all my teenage years, that as much as I revered the great accomplishments of European thinking and philosophy, equally as much I was appalled by the darker corners. In later years, this shame has turned into anger and then to commitment.

Having said that, I am eternally grateful for having read Roots. I am grateful that I learned that there is hope of breaking the mould, that things are not doomed or static, that the most powerful things in life are not always easily seen, and that they take time. And most of all I am grateful for having been shown that the ubiquity of human determination and intelligence can surpass and find loopholes in all constraints.

Which book turned your world upside down and why?