Posts in Category: 2011

Spew your lunch, your history and your language on me

Sofi Oksanen, I wish I could read Finnish so I could read your debut novel in its originality. Not that the translation was bad at all. It’s just… I feel there is something embedded in the language itself, that cannot be translated and understood at all. Like I have read a story that has so much cultural baggage, that this novel alone cannot satisfy my knowledge on the cultural/political aspects of this novel. And language (or expression) is a very important part of ‘Stalin’s Cows’. Language is identity and culture, it is something that both manages to distinguish you from and unite you with others on different levels. And when there is so much stigma attached to your heritage you go on the fence. But the narrative is interspersed with snippets of utterances in Estonian, Russian and Finnish that arrest my journey. And so the whole idea of denying someone the use of language, the right to express through language a part of one’s identity, proves to be futile; it wants out, it gets out, it finds ways no matter how hard you try to cover it up.

Sofi Oksanen, if I wanted to do my project justice I would sit myself down with an encyclopedia (old school), history books, essays on cultural transposition, and a dictionary, so I could tear the novel apart and let it percolate through my mind. It’s not just the words, but the enormous baggage and memory that lies behind them I want to get to. There is literature that wants to investigate itself on its own premisses, and then there is literature that needs words to give up their own agenda and become translucent – still autonomous, but hinting at another level, often in need of a personal voice, a subjective form to utilise language. And then, language is really just a conveyor belt.

Sofi Oksanen, the way you decide to delve into the logic of an eating disorder fascinates me. Dealing with it all cool and distanced, on a theoretical level, a tour de force in self-delusion, you chose latent communication. What does ‘Stalin’s Cows’ want to say? Is self-preservation, the physical minimum-survival-excistence, above all other aspects of life? If you spend your whole time making escape routes, creating a persona or shell, denying your identity in the process, the most engaging part of the day will not be how to live in the world, but how to endure yet another day in your own body. The logic of the eating disorder spirals through and through in Anna’s obsessive expositions and the language of food consumption and paranoia shrouds every day, every encounter, every meeting and flashback.

Sofi Oksanen, thank you.

Electronic, conceptual, visual, concrete, structural literature, literature, literature

Last week another semester started at uni, and this time I will be delving into the vast field of literature as more than just the piece of text inside a book. On Thursday we were introduced to the semester plan and the curriculum with bonus literature.

The course is really fascinating. When I first read the course description I didn’t really know what to expect, and only had a vague idea of what the “expanded field” of literature covers. I have talked about the e-book before on my blog, but more as a concrete tool for reading a piece of text without anything extra to it, or introducing the possibilities that come with an electronic book. The e-book has spawned new directions for literature and at the same time reintroduced the book as physical form and an integral part of the context where no text can stand alone.

One take on the e-text is taking advantage of the multi-touch function of smartphones or tablets. Aya Karpinska has created a children’s story, a so-called zoom-narrative, where you use the zoom function to maneuver around in the story. It’s an app that can be downloaded to your iPhone, and there you can explore and create your own paths through the narrative. The story is called Shadows Never Sleep and there is also a demo video.

In the physical realm there are creations such as Jonathan Safran Foer’s latest book, Tree of Codes, which combines the visual and the tactile with the cognitive. There is more than continuous text on page after page after page. What he’s done is he has taken a novel by Bruno Schulz and made his own story out of the already-existing words by cutting chunks out of the “original” and the pages therefore are fragmented. It is a piece of text that is much more, that takes into account its physical presence.

Cue hypertexts and the children of the digital age, children in a way that you get to play with the internet, try its boundaries and piss people off by not abiding to rules and regulations. Today (and I have like 143 tabs open, my computer is ready to give up, and I don’t have enough time in the day to read all of them, so I am on a continuous journey that takes me longer and deeper into different corners of literature+art+internet) I found Jane Wong/Joe Davis with Ways to carry you, and Jason Ockert/Mattias Dittrich Shirtless Others. I will not say to much about it, except invite you to try it, see what you think. And then there is Kenneth Goldsmith’s Soliloquy, which is an unedited transcription of everything Goldsmith uttered in one week of his life. It’s quite funny to browse through.

UPDATE: I keep finding new stuff, but this last one is so good I have to make an update and include it: it’s Seoul based web-art group Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries. They make text animations with funky music, you have to check it out. I stumbled onto Dakota (a reading of Ezra Pound’s Canto I & II), which is linked here, and a transcription here, but there is much more if you go to the mainpage: http://www.yhchang.com/

I picked these (sorry) almost at random, just as an introduction to the vast amount that is just lying out there, and all my tabs are waiting, nay pining, for me to explore them (as I assume, of course, my tabs have emotions resembling that of humans, and not, as I heard at a party, fish, who have no feelings and thus can be eat by vegetarians, over and out).

All the people

I read in an article recently that it took us several hundred thousand years to go from 0 to 1 billion people, and only 12 years from 6 to 7 billion which is expected to be the count for the world population in 2011. So many people, everywhere, and a number that is growing so rapidly, has gotten many people seriously questioning the prospects of sustainability and life quality. It is estimated that 1 billion people suffer chronic malnutrition and many more are just scraping by, affected by floods and other climate disasters that countries are unable, in one or several ways, to help their citizens survive. At the other end of the line, where the life and death scenario is not an immediate issue but where people are struggling to find meaning of their existence in this big world, you have the misplaced, the in-betweens, and the getting-by’s of Western so-called developed countries. Someone has said that we are losing touch with compassion, empathy and solidarity across the board the last decades, that our trip to individuality has left us so me-me-me fixated that we cannot see past the tip of our noses if it doesn’t apply to us in an immediate fashion.

I got a call from Amnesty yesterday. It was a person on the other end who first thanked me for my contributions in the previous year and then told me that they could use more help if I was up for it. He then went on to talk about a specific place where my contribution (they never say money, maybe it is just to dirty a word, to acknowledge that our society has built itself around currency) could do good, namely Haiti, where women are raped in greater numbers than ever before due to the lack of control and corruption that leave the police at best indifferent (his words) to the women’s suffering. Finally he asked in a meek voice if I thought that I had some way of making room in my budget so I could possibly up my contribution a little bit, so they could do more humanitarian work. When I said yes to his suggestion he sounded so genuinely happy, that I felt really ashamed that I had not suggested a larger amount of money. And then surprised by this. Now why on earth was I not just happy to contribute?

And why mention this in a book blog? Well, I have had these kinds of thoughts with me while I read Harstad’s ‘Buzz Aldrin, hvor ble det av deg i alt mylderet?’ (English title: Buzz Aldrin, what happened to you in all the confusion?). Maybe it’s a bit weird to introduce Harstad’s novel with these two very concrete examples, since it is not a book that deals with natural disasters, famine or (over)population. But it deals with the one in the masses of humanity, and what effect they have on others, what sort of chain reactions lead on lifeline over to another. For me Harstad’s character, Mattias, is a central contemporary voice of those in-between’s. He is also the One in the book – the individual, the center of causality. But even so, it is not an egomaniac who fills the pages. You feel like slapping him for his apathetic and apologetic nature, and yet you sympathize and identify with him. The novel centers around a person who is dislodged and alienated from himself, his family, his girlfriend and society so much, and just wants to fizzle out in the great vast ocean of people, to not attract attention or make a fuzz, that he ‘flees’ from Norway to the Faroe Islands. A place where no one knows him and he knows no one. In this postmodern, fast-paced lifestyle he is one person who does not feel or doesn’t want to feel the drive of a winner, a top-competitor, someone who strives to be the best, at one point it states that he wanted to be the best second-best or runner up. He just wants to get by, to fill some service void, and get on with it. At the same time he is caught between two places, because he is aware of the fact that he doesn’t want to disappoint those who are close to him – he is scared to oblivion of being useless, of being in the way. He creates a buffer around his person and all around him. But on the Faroes he discovers a group of people (or rather they discover him) who take him in – at a psychiatric half-way house – and he connects with them. They are in a way embodiments of his own fears, and at the same time mirrors of his situation. Together they form a society of in-betweens.

It’s not very often someone from outside the Faroe Islands sits down with a pen and starts writing a novel using the islands as a backdrop. And in a way it feels very strange reading this without giving way too much attention to the scenery when you know Klaksvík, stood freezing in a bus shelter on Hvítanesvegur and drove too many times around the islands in a car because there is little else to do when you are uninspired. And if I am not much mistaken, the photo on the cover is of the road to Gomlurætt – a symbol of a halfway place between modern city and quiet home town. Always covered in fog – timeless. Very symbolic! But then again, it is not a story of the Faroes but of Mattias and all the people.

The style of narration is exquisite, so vulnerable and rambling at points and concise at others. Some parts of the book have sentences that go on for 2-3 pages without a punctuation, and you find yourself running along with this fast pace, this ‘have-to-get-it-out-no-matter-how-it-sounds’ pace. He describes with fervor the in-the-moment scenery that you make faces and places come alive in your head while you read instantaneously. I think it is also this in-the-moment moments that Mattias lives by and can cope with. The world is so big, there are so many people, all the people everywhere, that he chooses to focus on one person or one feeling at a time.

I will end with a quotation taken from a beautiful funeral scene, where Mattias is to sing (he is previously introduced as a very, very good singer, but rejects it because of the center stage character singing entails). It barely needs more introduction or else I will spoil it for people who would want to read the novel:

And the important thing is not what I sang, but that I did it, and the sound filled the room, it forced its way around the church multiple times and through our heads before it pushed its way through drafty walls and clock towers, half-open doors and the people who stood outside felt warm for a minute, they closed their umbrellas in sync and stood there silently as the sound lifted itself over their heads and laid down on Saksun like a fog no one had ever seen before and I heard people crying, I heard people who could no longer hold back, and the minister went to his quarters for a minute, Havstein took a hold of Carl and Carl was sitting with his eyes fixed to the ground and did not dare look at the mother and Anna held her arms around Palli and Palli looked straight ahead and Havstein smiled to me, Sofia’s mother closed her eyes and I sang more powerfully than ever before, I tried to lift the roof, I tried to force the beams holding the roof to loosen from their battened places and open the building up, I wanted for the model boat that hung from the ceiling to sail out and the organist was doing his best to keep up, kept the pace with the notes and crawled up the register as I moved further and further in the song and at one point I left the lyrics entirely the way it was supposed to be sung, but the organist followed, we left the music and the lyrics and it just became sound and the sound enfolded everyone of us in warm woolen plaids and got us aboard unsinkable boats and I carried us over the oceans and onto land in another place and held the last notes for as long as I was equal to, and afterwards it was so quiet that you could have heard a bacteria falling from the ceiling and landing on the floor.

Not even God himself could have walked soundless through that room.

Gender seminar – days 5 & 6

Well, the internet finally caved in, and I was left out of the digital grid the rest of the seminar, so this is a belated account of days 5 and 6.

5

The rest of the nominees for the Montana literary prize were introduced at the morning assembly. They were Pia Juul’s ‘Radioteatret’, Anders Haar Rasmussen’s ‘En bold ad gangen’ and Thomas Boberg’s ‘Hesteæderne’. With a small introduction to every work, and the committee’s nomination text, extracts were read to us, one of which (AHR’s) was read by the author himself.

Then came a talk on the sitcom ‘Klovn’ (Clown) by comedian Frank Hvam, and director Mikkel Nørgaard. Their show has, ever since it first aired on Danish TV2, gotten a mixed reception of approval, disbelief and critique and has contributed to the debate about men and women, their behavior and relationship to each other. There were two things I locked on in the talk. One was when Frank Hvam said that one of the explanations to the character Frank weird and toe cringing situations he ended up in (often with his girlfriend) was that men were brought up in a feminized space, where there was a shortage of role models, and therefore women in great part were to blame for these weaklings they ended up living with. While I understand that a relationship built on a woman trying to parent and control a man is not healthy, I was surprised by this harsh statement, because I got a feeling that he wasn’t trying to be a smart ass or generalizing the topic. It was as if men/women relationships and men’s self respect could be saved if women would just back off. There seemed to be a blind spot in relation to where the male role model fitted into this logic. The second thing was the statement; we leave the interpreting field wide open, so that each and every one can put their own reading on the show. Given the fact that the show is seen solely through a man’s POV and many see this show as proof of the askew relation between the sexes in favor to the female sex and that there is something completely rotten in the state of Denmark genderwise, it’s hard to stipulate that there is an open playing field on this subject. They explained that their work process was built more on observation, recreating scenarios they pick up on and letting all the interpreting in the hands of viewers. But I am not so sure that this is true of the very reasons I stated earlier on POV and feminized space. I started thinking about the lecture the previous day by Henrik Jøker Bjerre who said that irony was maybe not always so innocent as it cloaked itself to be, because with irony you could close any critique of the matter before it got started by stating it’s non-seriousness.

After dinner there was a panel discussion on the previously introduced nominees. The panel consisted of Lars Bukdahl, Camilla Löfström and René Jean Jensen. It was a bit weird listening to the panel discussing these books that I had not read yet, and I couldn’t really say if they made good points or bad ones, but there was no doubting that they felt the three nominations were valid. They talked about the different qualities each work possessed, like how there is a polyphony of voices in Juul’s ‘Radioteatret’ that deal with all sorts of problems, and how longing for something and remembrance is a recurrent theme – as a child Eliza C. longs for adulthood, as a grown up she longs for childhood – and there is a certain criminalistic undertone in Juul’s writings, there is something dark lurking in this very longing that keeps the text vibrant. They mention a passage in the text where Eliza C. and her mother talk about the ocean, where Eliza C. asks if the ocean is coming closer, and her mother replies, ‘not if you have been good’. About ‘Hesteæderne’ Bukdahl talks about a hard-boiled noir – reminiscent of Raymond Chandler. The language is ugly and the depicted society is in shambles. Everything is decomposing and poetry and prose are in a battle with each other. The anger in the text manages to be both diffuse and concrete. And finally there is the tennis-docu by Anders Haar Rasmussen whose style Löfström says is radically new from journalistic sports books across the board.

In the evening there was a concert with Jomi Massage. When we came into the music hall there was a girl with two huge braids sitting on stage surrounded by bird chirping. Reminded me of a Heidi meets Snow White meets Lady Gaga meets Danish milk maid. The concert was one hour long and consisted of this one person playing on piano, guitar, drums, and some sort of distortion/echo microphone. I talked to some people afterwards and most of them felt that she had a really good voice that they had wished she really played on instead of all the instruments.

6

And then came the last seminar day. We started with a two part critic’s salon where Tue Andersen Nexø and Elisabeth Friis lead in a debate about Josefine Klougart’s ‘Hallerne’ and Rasmus Graff’s ‘Folkets Prosa’. Klougart started the salon by reading from her book which was done in a rhythmic and raw fashion. While Friis made connotations to French literature and its lust literature (Marguerite Duras for example), Nexø was reminded of internet porn. ‘Hallerne’ is about a voyeuristic sado-maschocistic relationship between a man and a woman where dialogue is on the minimum. They have transcended language possibilities. The woman who is narrating is this empty, worn vessel that is very brutally described as something outside herself, as is the clinical depiction of the sex act. She is just available and the story becomes this cleansed physicality. The story alternates between the city which is alive and filled, and the apartment where the man and woman are in this dead and empty space.

After a break Graff read from his ‘Folkets Prosa’, a piece of conceptual literature built on phrases picked from the Danish-Danish dictionary of Gyldendals røde ordbøger. (As you can see on the picture, as a part of his reading, he is pointing straight at me at the time I took the picture, which led to me getting a bit flushed, ’cause of my “yes, I am taking a picture, but no, I don’t want you to know or notice it”-syndrome.) It was really fascinating because the more he read, the more the language opposed itself, made everyone so aware of itself and ended up being absurdly comical. Nexø proposed three types of reading strategies: looking for clues or constellations in the text, or as an ideological critique where you transpose a piece of text from one setting to another to give new meaning to language, or the last one where it says something about literature. Friis read a passage up where she had used the first strategy by underlining sentences in two different ways, and a language pattern arose from this single page that could be read as critical towards how we construct language and how we use it. Nexø remarked on the title that he saw it as an ironical hint at the language snippets taken out of the dictionary, because this was not the people’s prose, but rather the language of linguist nerds and academia.

After dinner Susanne Christensen, critic and columnist, held a speech on feministic and queer critique. The field of criticism according to Christensen is much better of going at its subject matter following a lust principle rather than a morally judgemental stance. With regards to queer critique it is a more subversive nature and can bring avantgarde into criticism – it does not confirm identities but alliances between identities. Queer opens up the possibility for men and women to be seen as individuals. She brought many good points to the table and added to the already stocked depository of gender debate issues from the last days.

This sixth day was also prize winning day, where the audience prize that we had voted on and Montana’s literary prize were to be handed. At 5 p.m. we made our way over to the music hall where we all crammed into a tiny, but very cozy intimate setting and awaited the big reveal. The first one up was the Montana prize and after a short speech given by Montana’s representative the winner was revealed: it was Pia Juul with ‘Radioteatret’. A visibly moved author entered with the soundtrack of applause and whistles and received flowers and the prize. Camilla Löfström and Elisabeth Friis held a speech explaining the pick and commended Juul’s style. Anders Haar Rasmussen won the audience prize which consisted of a case of champagne.

After this we all mingled, talked literature, prizes and ate appetizers while sipping champagne, waiting for the three-course meal that awaited us in the cantina. And a little after 6 p.m. we sat down to a feast that lasted several hours with singsongs, wine, lavish food and afterwards the party kicked in with dj DameUlove.

The seminar was at its end, and all the different inputs had been introduced and were now mingling around and inside us. I am truly looking forward to next year’s seminar already.

Gender seminar – day 4

After going to bed at half past 2 yesterday (on the 11th as this is written on the 12th) it was a pretty shattering experience hearing 14 sets of mobile alarms from 7 am to 8.30. I dragged my tush over to the breakfast feast that was awaiting in the canteen and drank about 14 cups of herbal tea. ‘Luckily’, day 4 was not so hectic and jammed with events.

One lecture by post.doc. Henrik Jøker Bjerre on the philosophical thought’s problems with gender, and an historical overview of gender and feminisms from the 70’s to the 10’s by Mette Moestrup. And the day was finalized with an hour of singing from the folk high school songbook in the meeting hall.

The lecture by Henrik Jøker Bjerre was intense and packed with ideas on the problem with thinking gender. He based his lecture on two main foci – that of Lacan‘s ‘Encore’ and Lilian Munk Rösing’s ‘Kønnets katekismus’. There was again as with Munk Rösing’s lecture a whole lot of Lacan’s idea of the Other – understood as when you define yourself by positioning yourself against the Other, and in doing so you risk excluding and subordinating the Other. In this case the man’s gaze upon the woman, inscribing her to specific traditional roles, both of religious, secular and biological forms. The critique is that instead of acknowledging the Other, you overlook the Other’s otherness, in order to inscribe onto the other your own desire and understanding of the Other as a way of gaining control. In the lacanian notion, you can never know yourself completely, and should never try to create gender in one’s own image. Bjerre criticized the notion of discussing gender problems either with using non-gender logic or a polarization of the two sexes, whereas he sees a possibility in recognizing the difference between genders – the Otherness of each other – as a way of transgressing the deep problematic function of inscribed and traditional gender roles.

Moestrup’s lecture was interesting in the sense that I was introduced to a fascinating woman I had not heard of before: Hannah Wilke – a performance artist who used her body as a tool for her ‘message’. See more on her here. Maybe I was too tired at this point, but I couldn’t really sink into the lecture she gave, but she spoke a lot about the lies which we reproduce over and over again about gender and it was also here that I became aware of Cixous who wrote ‘The laugh of Medusa’ which is now officially on my ‘to read after seminar’-list.

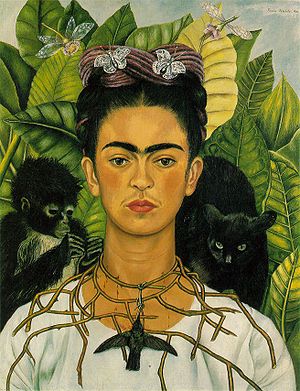

The introduction to Wilke coupled with the lecture about queering by Dag Heede made me think of another female artist, whom I am fascinated by; namely Frida Kahlo. It was especially when Moestrup talked about female artists and the question of historical hierarchisation between the sexes, where woman is object/form and man is subject/artist. Because what sometimes happens when woman decides to be artist; she uses herself and thus becomes both subject and object. This is true of Frida Kahlo, who spent most of her time portraying herself in various situations – situations, that were both painful (as the painting of her in a hospital bed after a recent abortion), and mysterious (where she combines nationality, her Mexican heritage, in with the political ideology and gender). Below are a couple of her paintings.

In the evening a bunch of us met in the lecture hall and sang songs from the folk high school songbook, which was very cozy although I hardly knew the songs we were singing. It didn’t matter, because I started to get a nostalgic feeling towards my time at my ‘ungdomshøjskole’ that I spent half a year at, way back in 1999. Songs are a very strong traditions at folk high schools, the whole ritual of singing is well embedded in everyday life. And it was so weird because the head of this school reminded me so much of my old headmaster where I was, somehow it’s the folk high school way.